Difference between revisions of "Between the living room and the kitchen: new music in Salazar's Portuguese totalitarian regime between 1958 and 1968"

From Unearthing The Music

Diogooutra (talk | contribs) m |

Diogooutra (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

| − | [[Category: Portuguese Content]] [[Category: | + | [[Category: Portuguese Content]] [[Category:Articles]] |

Latest revision as of 21:36, 6 April 2021

The following is an essay by pianist, composer, teacher, researcher Francisco Monteiro regarding the state of avant-garde music Portugal under the Estado Novo regime.

‘Between the living room and the kitchen: new music in Salazar's Portuguese totalitarian regime between 1958 and 1968’

Twentieth-century Music and Politics

Department of Music, University of Bristol

14-16 April 2010

Contents

Introduction

Portuguese society in the sixties was influenced by different movements that marked its culture during the next decades. These movements shocked society in many ways; but, in what concerns avant-garde music, it seems that they were somehow tolerated - and neglected - by the official institutions, supported only by the private ones. The aim of this paper is to understand the reception of avant-garde music between 1958 and 1968, and to compare it to the rigid, conservative controlled state and society.

I – The Estado Novo

First of all it is important to highlight the long dictatorship of the Estado Novo, having as Prime-Minister Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970) since 1932. Salazar’s regime survived the Spanish Civil War, World War II, and the colonial war after 1960 (in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea Bissau) barely untouched. Salazar would have an accident in 1968, being substituted by the also conservative – but more development friendly - Marcelo Caetano. The dictatorship was marked by institutions such as the allowed National Party (União Nacional), the youth paramilitary organisation (Mocidade Portuguesa, created with help from Germans of the Hitler Youth), the civil militia (Legião Portuguesa), the political police (PVDE, later PIDE and DGS) and the official censorship (Comissão de Censura)1. In what concerns music, the following entities were highly important: the National Radio (Emissora Nacional) that supervised several orchestras (symphonic orchestras in Lisbon and Porto, the entertainment orchestra and the folklore orchestra), a Ballet company (Verde Gaio) and even a musicology studies bureau. Also very important was the S. Carlos Opera House, considered the “living room” - or rather, the “visiting room“ of Portugal 2.

It is interesting to consider a 1964 speech made by the Secretary of the S.N.I. - National Information Secretary - Moreira Baptista, referring ironically the artistic avant-garde movements and their repression:

"Also interesting are the references to the so called “revolution”, referring to the "Estado Novo coup d’état" that ended the democratic republic in 1926 and the assumption of the “reactionism of the regime”, the ”bourgeois conception of intellectual expressions”, and the “oppression of the free expression of thought”".

Music in Portugal between 1958 and 1968: some interesting events

To understand the reception of musical modernity and avant-garde, all musical events of the period in question between 1958 and 1980 were detailed, together with critics, reviews and other sources. In this paper, I chose to highlight some specific events that seem to be striking and emblematic.

Year 1959

Musical life in Lisbon was, at the end of the fifties, becoming more and more at the same level of other major cities of Europe. In 1959, the second Festival of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation invited major artists such as Isaac Stern, John Barbirolli, Walter Süsskind, Brailowski, Starker, Giulini, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, and others. But in what concerns modern music, some specific aspects were relevant:

- Twelve-tone music and new music in general were being much more played and discussed in articles, interviews3 and in lectures organised by private institutions;

- Musique Concrète and electronic music began to be played and discussed in Portugal, when Maurice Béjart came to Portugal to dance Pierre Henri and Schaeffer's Symphonie pour un Homme Seul, and when João de Freitas Branco gave a lecture about electronic music in Lisbon4;

- The first twelve-tone compositions appeared (Álvaro Cassuto’s Short Symphony n. 1 and Sonatina for piano and Jorge Peixinho’s Five Small Pieces for Piano); Jorge Peixinho went to study in Rome and made contact with Europe’s avant-garde music.

Year 1961

In November 1961 a major event happened in Lisbon: one concert by the avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen and another with the pianist David Tudor. Tudor played avant-garde works in a recital with introductory words of the young Portuguese composer Jorge Peixinho (1940-1995). Stockhausen gave (November 22nd) a concert with instrumental and electroacoustic works, with music by himself and his student Caskel. These concerts were preceded (20th November) by a lecture given by another young Portuguese composer - Armando Santiago - in the Lisbon Conservatory. Both concerts were sold out, with noisy opposition from some part of the public.

These events had an enormous impact on some of the young musicians present: the young student Emmanuel Nunes was overwhelmed by the sounds and ideas presented in these concerts. From that day onward, he began to search for new music, records, scores, and finally went abroad and studied new music.5 Emmanuel Nunes is now a leading Portuguese composer, well known in European festivals.

Stockhausen's visit also led to a TV programme. The composer Filipe de Sousa, who was working at the Portuguese Television (RTP), produced a large programme (with music and interviews) about this German composer. Álvaro Cassuto – another young composer and introducer of twelve-tone music, translated this interview.6

Year 1964

Contemporary music witnessed an important development this year. In January — continuing until April — a series of lectures on modern music began, organised by the Students Union of the Law Faculty of Lisbon, the Beaux-Arts National Society, the Goethe Institut, Gulbenkian Foundation and the J.M.P.

The influence of Jorge Peixinho continued to increase, as a composer, as a teacher and as a performer. He organised a concert (6th November) with, among others, a first work of Emmanuel Nunes (première of Conjuntos I 7). As Álvaro Cassuto — acting as a critic — reports8, a big debate grew about this concert: Cassuto refers to the need for a strong and effective musical education of young people. In fact, the (Portuguese Jeunesse Musicale) organised a debate session, which discussed mainly John Cage and his work.

Filipe Pires saw in November his new work Akronos played by the E.N. orchestra. Part of the public, according to Ruy Coelho — acting as a critic — reacted in protest against this piece with hissing and hooting. In a review in the Diário de Notícias, Ruy Coelho says that: "It's written without barlines (...) far too monotonous and antimusical (...)".9

Filipe Pires was this year invited as “Artist in Residence” in Berlin (6 months) at the invitation of the Ford Foundation.

In fact, 1964 is a summit in terms of the appearance of new music: many new pieces and composers were heard, many lectures and debates on contemporary music were given, reviews were discussed in the newspapers, many Portuguese new works were performed. And, at the same time, Ruy Coelho's new opera Orfeu in Lisbon debuted to the applause of the state and the press.

Year 1965

As in previous years, great musical names were invited. But, on the 7th January, a group of artists produced a "Concert and Pictorial Performance", in the Divulgação Galery10 in Oporto. It was the first happening in Portugal 11. The programme demonstrates the character of the event:

Cartridge Music — John Cage

In the First Interval will be heard, as background music, The Funerão of Aragal12— António Aragão

Piece 59 (negative music) — E. M. de Melo e Castro (world premiere)

The Black Door — Jorge Peixinho

Zzzzzzz.................Rrrrrrr!... (this piece would not be presented because it provokes sleepiness)

Suite for Toy Piano — John Cage

Electrowails — Jorge Peixinho

"Sonata ao Lu...Ar Livre" 13 (this piece will not be presented here because there is no "ar livre"14)

In the Second Interval: Spotlight and Noise

Meter Concert; Balophonia — with the participation of the Human Spirit

Bidographic

Extra. program (if there's an extra):

Aria to the Critic — Salette Tavares (performer and author)

The sequence of the program will be changed for the following (un)previewed motives:

____

____

____

Interpreters: António Aragão, Clotilde Rosa, E. M. de Melo e Castro, Jorge Peixinho, Manuel Baptista, Mário Falcão, Salette Tavares.

Melo e Castro reports that Jorge Peixinho played violin with a firearm and drank champagne from a bidet, Salette Tavares sang an aria to the cri-cri-cri-tic, António Aragão played lying down in a coffin, and Melo e Castro turned 1000 Watts spotlights onto the public. The improvisation was incredible, as was the excitement and/or anger of the public.

With the same kind of provocation, the group Zaj15organised on the 27th of February in Lisbon an exhibition of the artist Millares and a concert with works by Hidalgo, Marchetti and Barce.

1958-68 – an overview

Performances and the Public

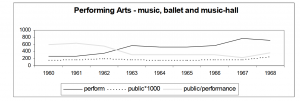

A positive evolution in musical performances can be seen in a study by the social researcher António Barreto on Portuguese society16, which shows an increase in music, ballet and music-hall performances between 1960 and 1968.

Unfortunately, the graph shows that this increase didn't mean more people going to these performances.

Modern Composers

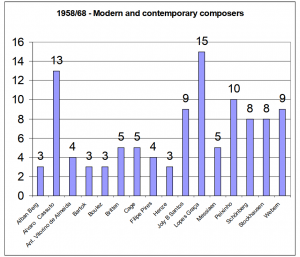

The Portuguese leading contemporary composers were occasionally played by the different orchestras and soloists. It is interesting that the graph shows that the composers with more performances were Lopes-Graça, Alvaro Cassuto and Jorge Peixinho: Lopes-Graça was a neoclassic composer and an intellectual, member of the communist party, banned of all official institutions by the Regime, but permitted to travel abroad representing Portuguese composers in the ISCM; Alvaro Cassuto was a young composer and conductor with interest in new – twelve-tone – music; Jorge Peixinho was the leader of Portuguese avant-garde music.

Among the more traditional composers, Ruy Coelho was performed constantly in Portugal and abroad and also recorded; he was praised by the regime with medals and prizes. This composer and conductor was, in fact, a constant in the S. Carlos Opera and in symphonic (also choral symphonic) concerts (Symphonic Orchestra of Lisbon): every year there is a reference to symphonic and choral symphonic pieces played in Portugal and/or abroad; also in 1960, 1964 and 1966 new opera productions of different works were performed.

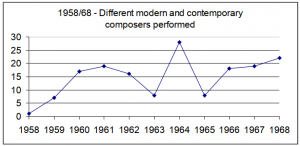

The evolution from 1958 to 1968 must also be considered. The picture above shows this increase in terms of the number of modern and contemporary composers performed in Lisbon, showing some particular years: 1961, 1964 and 1968.

It seems that 1968 is a turning point in Portuguese and world history: Salazar's accident and the emergence of the new Portuguese Prime-Minister Marcelo Caetano, the student unrests in Portugal, France and U.S.A., the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Red Army, the preparations at N.A.S.A. for the voyage to the moon (in 1969). In Portuguese music, three composers of this young generation, for various reasons, stayed out of Portugal for some years: Armando Santiago moved to Canada; Álvaro Cassuto began to work as a conductor in the USA; Álvaro Salazar, went to Brazil as a diplomat.

If, in Portuguese avant-garde music, 1958 till 1968 was, perhaps, the decade of the reception of avant-garde, with the emergence of these composers, the next years would be marked undoubtedly by the — already very influential — personality of Jorge Peixinho and the emergence of his GMCL (the Contemporary Music Group of Lisbon).

Conclusion – Between the living room and the kitchen

Between 1958 and 1968, music in Portugal, especially in Lisbon16, was subject to an enormous development due to an increasing number of concerts and to the presence of more musicians and groups of an international standard. In fact, Lisbon became more and more in the middle of the international classical music circuit, well served in terms of the world's most famous opera singers, concert pianists and violinists. The Portuguese “living room”, symbolizing not only the S. Carlos Opera house but also all conservative music events, was reinforcing the cultural status quo - indulgent, bourgeois, compromised, glamorous events; but the kitchen – here symbolizing the noisy, new, peculiar, uncompromised music – was effectively showing its importance.

The regime never really persecuted the new and the avant-garde, except if the new meant an explicit compromise with political ideas: Brecht was commonly censured, words like democracy were banned, the private correspondence of Portuguese composers were read by political police officers, and some avant-garde artists had special files in this police relating their behaviour. Lopes-Graça – the known communist neo-classic composer banned by the regime – was constantly played by private institutions, and allowed to go abroad representing Portugal in the ISCM. But Lopes-Graça was known also as a heterodox communist, criticising in texts the conservative positions of composers like Prokovieff and Shostakovich; and someone with no power in the underground Communist Party.

In fact, the kitchen – symbolising the new, the avant-garde, the unusual sonorities - never put the conservative music milieu in danger, symbolised by Salazar’s living room – the S. Carlos Opera house. The kitchen stayed in its corner as an illness of young, left radical intellectuals, or as a bunch of shocking events with no importance in the “real” musical and artistic world, with only a few followers, well controlled by the intelligentsia, the state police and the authorities.

Or perhaps not:

- Some of the young army members and intellectuals that were very influential in the revolution in 1974 and the next years were usually in these avant-garde concerts and other private cultural events;

- We see in the last two decades to an enormous growth in Portuguese composition; perhaps a growth only comparable to the generations of Portuguese composers of the 16th and 17th centuries; this new generation is, perhaps, the result of an evolution that slowly began in those hard days of the sixties.

Notes

- See Oliveira, César (1990): p.13 and following.

- See Freitas Branco (1982): p.60.

- See Arte Musical (1958 - n.3), interview with Maria de Lurdes Martins; see Cassuto, Álvaro (1958) and Cassuto, Álvaro (1959), papers of about the twelve-tone system; see Lopes-Graça, Fernando (1992 a):page 116.

- See Arte Musical (1958 - n.3).

- Cf. Nunes, Emmanuel (1998): page 13.

- According to personal conversations with Filipe de Sousa.

- A work now out of catalogue. Cf.- Diário de Notícias 7/11/1964, Arte Musical (1967 – n. 25/26).

- Cf. Diário de Notícias 7/11/1964.

- Cf. Diário de Notícias 9/11/1964.

- Now the Leitura bookshop.

- Cf. Melo e Castro (1977): page 59.

- A play between the Funeral and the name of the author Aragão.

- Free Moon-light Air Sonata

- free air – open air

- A Spanish group of contemporary artists of different disciplines, connected with J. Cage, D. Tudor, neo-Dadaist and Surrealist groups and artists. Some of the participants in Zaj performances (exhibitions, recitals, "concert-parties", "events", etc.) were John Cage, David Tudor, Walter Marchetti, Ramon Barce, Juan Hidalgo, Tomás Marco, Alejandro Reino, Manolo Millares, José Cortés, Manuel Cortés, Eugenio Vicente, etc.

- Cf. Barreto, António (1996).

- The data that was collected for this research reflects mainly what happened in Lisbon. In fact, the rest of the country had no relevance concerning contemporary music.